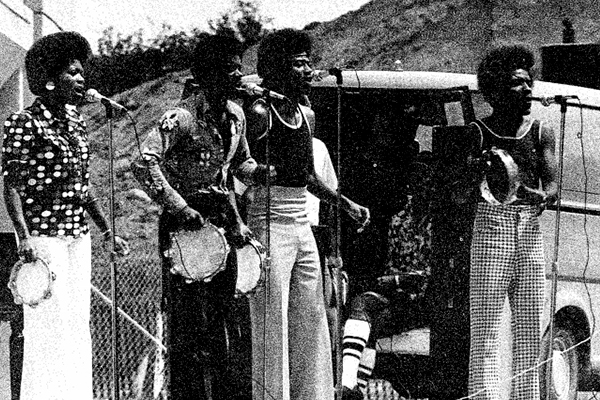

A photo of WCC students featured in the course catalog from the 1975-76 school year. WCC Course Catalogs Archive

By Samadhi Tedrow

Contributor

As we are deeply seated into the month of February, it is important to acknowledge the rich African American history embedded not only in our nation, but right here at WCC.

WCC in ’60s and ’70s

In 1965, the college was founded. Three years later, in 1968, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, prompting protest and demonstrations on campus by students, according to Cynthia Reynolds Furlong in her book “A Fierce Commitment: The First 10 Years of Washtenaw Community College.” State police brought in undercover policemen in response to protests, said Furlong.

Also that year, according to reports from the Ann Arbor News at that time, students petitioned to name the WCC student center after King, and thus was born “Martin Luther King Hall.”

In 1969, members of the Black Student Union presented a list of demands to the WCC president at the time, David Ponitz, according to Furlong. The list prompted changes that helped humanize African American students with new vocabulary and social reform across the campus. These were the first steps to black empowerment within the college’s walls and bolstered the foundation of a Black Studies program at the college. The black studies program featured courses including “Afro-American Music,” “Black Literature” and “Black Psychology.” Later, as the program expanded, other classes were offered, such as: “Black Economics,” “Black Politics,” “Black Drama,” “Black Woman,” and “Media and the Black Community.”

Despite this victory, there were still turbulent times for social justice at WCC. In 1969, the faculty union cast a “vote of no confidence” in Ponitz due to “problems of black students in achieving their rightful place in the academic community,” said Furlong in the book.

In 1970, the Black Student Union returned with updated demands for the college president, pushing for better development of the Black Studies program, a Black Culture Center on campus and a Black Review Committee to review African American financial aid applicants, according to Furlong. Also included was the need to do away with ununiformed police in campus buildings.

The Black Student Union supported African American history, literature and culture at WCC, while remaining a stalwart defense in the student body alongside other civil rights protestors. At the time, the WCC student newspaper quoted an African American student who said, “They (white people) can interpret our demands any way they wish. All black students in America are fighting for the same thing—and we ain’t gonna run.”

In Furlong’s book, a professor at the time, Edith Croake, is quoted as saying, “I was impressed by how community members were willing to risk their safety, guarding the new Community college.”

In 1981, Black Panther Stokely Carmichael spoke on campus, according to reports from the Ann Arbor News.

Black history across the globe

Kimberly Jones, a professor of black literature at WCC, said, “African American history is meant to find commonalities among other cultures.”

She said that there is much more to African culture and it stems into the deeper annals of history than just slavery and the creation of the Emancipation Proclamation.

“Societies and systems in Africa were highly complex,” Jones said.

Jones said the root of unjust stereotypes placed on the black community are a result of a long line of forced cultural appropriation that ultimately stems from European settlers.

The diverse range of courses and activities that celebrate black culture are meant to break the stigmatization of stereotypes, and the inclusive environments we see now are thanks to the powerful proactivity of early faculty and students who spoke loudly during times of racial injustice.