Bombers lined up near the end of production at the Willow Run Bomber Plant, circa 1942/1943. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

by ELINOR EPPERSON

Contributor

Eighty years ago this month, workers began clearing land near a small creek in Ypsilanti Township to make way for the largest factory in the world, the Willow Run Bomber Plant.

The factory prompted the creation of the Washtenaw County Health Department and was a key part of America’s “arsenal of democracy.” But before Willow Run produced almost half of the bombers credited with changing the course of World War II, it followed a long and winding road of obstacles.

The bomber plant’s story began before the United States even considered entering World War II. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, having spent the majority of his previous two terms implementing the New Deal, was watching the conflict in Europe with unease.

Roosevelt, who was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War I, began his third term as president asserting that the United States needed to build an “arsenal of democracy” to fight for human rights worldwide. Mounting invasions by the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) had ruled out negotiations. Roosevelt believed that airplanes were paramount to win a war of this scale.

“If you don’t control the air, you can’t control the ground,” says Randy Hotton, former Navy pilot and volunteer at the Yankee Air Museum since 1985. Air power was “essential” to the Allies (Great Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union, China, and France) during WWII, he says.

Hotton flies the museum’s Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the predecessor to the bomber Willow Run built. Visitors can reserve private sight-seeing flights on the plane named “Yankee Lady.” Hotton clocks about 50 hours of flight time on the plane every summer.

When he’s not flying, Hotton is also a historian. He is the co-author of “Images of Aviation: Willow Run,” a pictorial history of the bomber plant. Hotton was inspired to learn more about the plant because his father worked there and because of his own love of aviation.

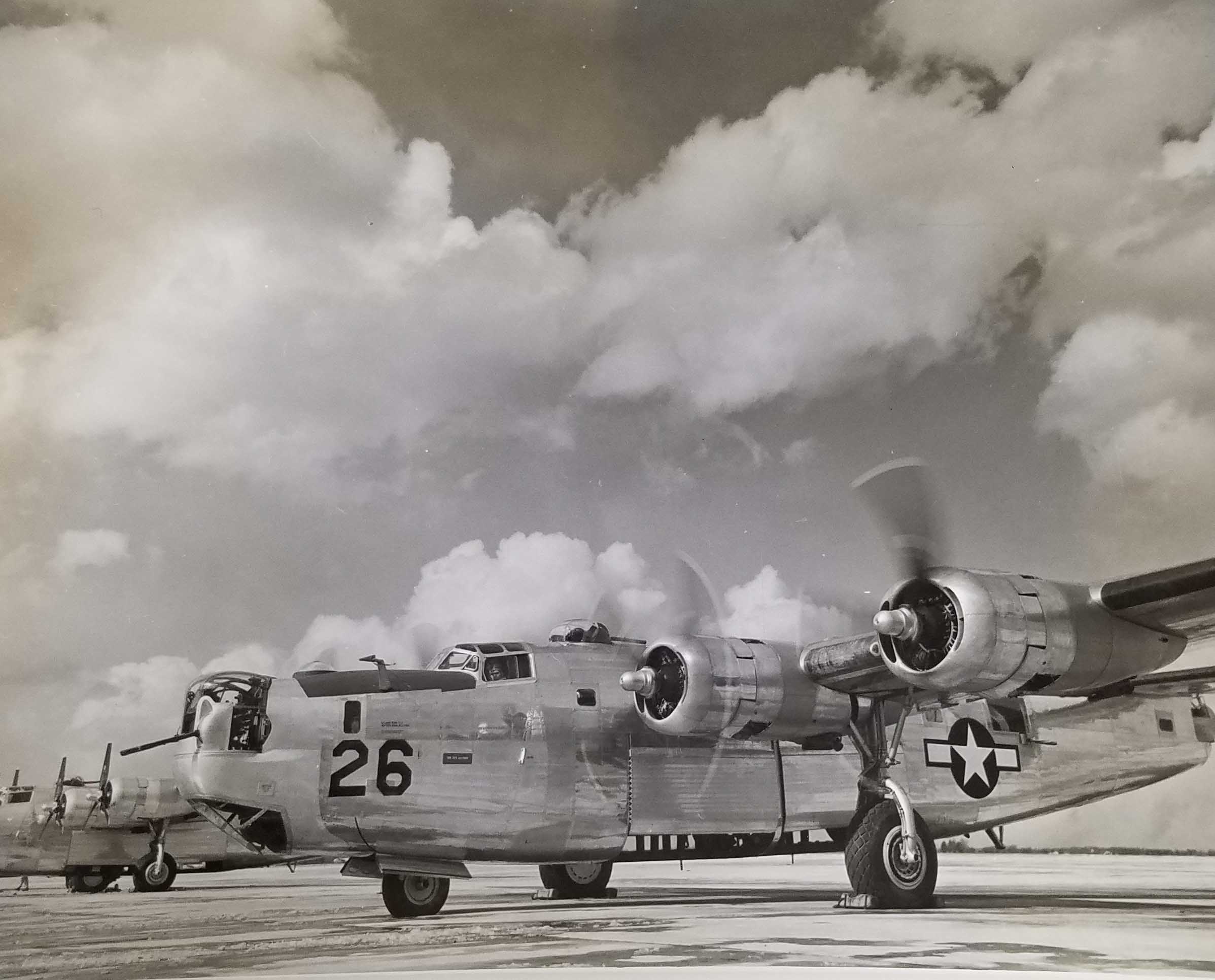

Willow Run was integral to the nation’s arsenal of democracy because of what it built: the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the most-produced heavy bomber in history.

A B-24 bomber sits on the tarmac at Willow Run, year unknown. Courtesy of Ypsilanti Historical Society.

Before World War II, the US had the 18th largest military air force. The few planes the U.S. had couldn’t compete with the German Luftwaffe (air force), which had hastened Germany’s 1939 conquest of Poland with their relentless bombing campaigns. Hotton says the U.S. only had about 500 “modern” planes at that time – certainly not enough to support the U.S.’s allies in Europe.

Consolidated Aircraft, an airplane manufacturer based in San Diego California, submitted designs for the B-24 Liberator to the Army Air Corps for consideration against the Boeing B-17 (the U.S. Air Force would not be incorporated as its own branch of the military until 1947). The government would end up producing both, but the B-24 could fly further and drop more bombs than the B-17.

The new B-24 was “so superior to the B-17,” says Hotton, that the government wanted thousands of them, and quickly. When the federal government approached automakers about manufacturing parts for the new plane, Ford Motor Company promised to build one bomber per hour.

Going into the second world war, Ford had a reputation for manufacturing prowess. The automaker had pioneered the production line assembly of cars in the 1910s and hoped to apply the same process to airplanes.

Before Ford’s bomber plant, no one had assembled planes en masse; they were all manufactured and put together one by one. This cost more money, took longer, and produced planes with wildly ranging specifications. Ford promised they could build airplanes cheaper, faster, and better.

The federal government was itching to jumpstart the production of war-ready planes. They had originally asked Ford to manufacture parts for the plane and send them to other plants for assembly, but Ford production manager Charles Sorenson insisted that the automaker build the entire airplane.

Interior shot of the Willow Run Bomber Plant under construction in December 1941. Courtesy of the Ypsilanti Historical Society

But behind the scenes, Ford was not ready. Building, staffing, and operating a plant so large took a few years to master, earning the plant the nickname “Will It Run” in its infancy.

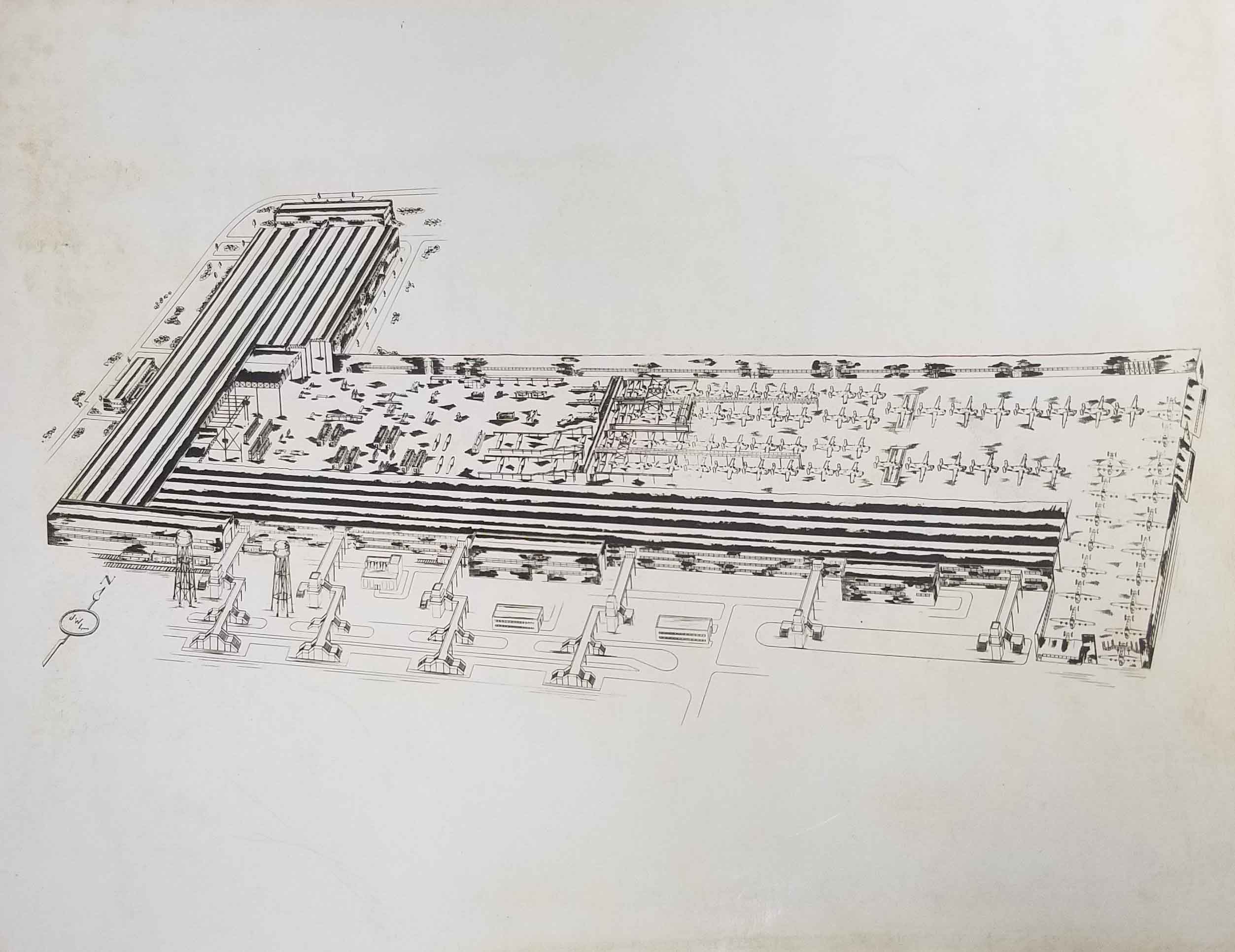

The adjacent airfield with three runways (now Willow Run Airport) was constructed quickly in 1941, only to sit empty for 10 months while the bomber plant caught up. The size of the plant ballooned from initial estimates of 858,000 square feet to almost 3,000,000 square feet. Ford had to hire five different construction companies to build the plant in five sections.

To accommodate the manufacturing of parts and assembly of planes that were 67 feet long and 110 feet wide, the assembly line had to be over a mile long. Ford discovered during construction that this would take the plant over county lines into Wayne County. The plant designers added a 90-degree turn at the last minute. Called the “tax turn”, this architectural decision was made to avoid paying taxes in two different counties.

Drawing of the plant, including the assembly line, date unknown. The “tax turn” is on the right. Courtesy of the Ypsilanti Historical Society.

While the plant was under construction, Ford discovered that Consolidated didn’t have updated blueprints for the plane. The automaker sent engineers to Consolidated’s headquarters in San Diego to draft blueprints themselves. The process took four months, with engineers producing five miles of blueprints per day.

Consolidated and the Army were constantly updating the plane’s design. Between September 1940 and December 1941, the Army Air Corps released eight design changes to the plane, hampering Ford’s efforts to plan the manufacture of parts and construction of the plane. Design changes would continue to delay and even halt production after the plant opened.

Despite these obstacles, the plant was built “in record time.” Within 14 months of breaking ground, the first Ford-made B-24 rolled off the assembly line in Willow Run. It would be another two years before Ford fulfilled its promise of one bomber an hour.

Everyone (Ford, the federal government, and even several Ypsilanti city officials) assumed new workers would commute to the plant rather than move to the area. A five-mile commute was normal at the time, especially with Henry Ford’s philosophy of “every man a car owner” taking hold.

But with Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war came rubber and gasoline rations. Commuting from the Detroit suburbs was suddenly out of the question, and Ypsilanti was far from any other major population centers in Michigan and Ohio. Workers began descending on the small town and found nowhere to live.

Before the bomber plant, Ypsilanti had a population of 12,000. Most citizens worked in agriculture or education, as the city was home to the Michigan State Normal School (now Eastern Michigan University). Ypsilantians didn’t think of themselves as being tied to Detroit or the auto industry, and the area was more rural than suburban.

The federal government was keen on building plants away from the coasts, which were prime bombing targets for the Axis. And Ypsilanti had acres of land, much of which was owned by Ford. The fields adjacent to Willow Run, a small creek known only to the locals, were the perfect spot for the mammoth facility and airfield.

To prepare for the expected onslaught of new workers, Washtenaw County formed its own health department. Officials anticipated the influx of people would bring an influx of pathogens, sewage, and other problems that threatened the health of everyone in the city. But nothing was done to address the impending housing crisis.

At its peak, the factory employed over 42,000 workers – more than three times the population of Ypsilanti. Workers streamed in from out of town, coming from all 48 states.

But there was nowhere to live. Workers constructed tar paper shacks in fields, slept in chicken coops, and practiced “hot bedding,” which involved sleeping in “shifts” on the same bed as fellow workers. Others lived in partially-constructed basements, called roughed-in housing.

There was limited housing for single workers, but family housing was even sparser. One worker, a widow named Rose Monroe, moved to Michigan from Kentucky to work at the plant. She lived in a worker dormitory while her children stayed with family friends in Jackson. Monroe’s children visited her on weekends.

Shacks and lean-tos that served as shelter for workers circa April 1943. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Worker turnover during the first year of production was enormous. Workers had nowhere to sleep comfortably and more men were enlisting in the military. At the start of 1943, Ford was hiring 1,800 workers per month while 1,600 left. The cost and time devoted to training new workers, only for most of them to leave, was crippling the plant.

New housing didn’t appear until spring 1943, mostly in the form of temporary housing built by the Federal Public Housing Authority. The FPHA was created in February 1942 by a presidential executive order to manage federal public housing but didn’t reach Michigan for another year.

Housing projects in the area included dormitories for single workers as well as family housing, such as Willow Village and Pittsfield Village (now Village Cooperative Homes off of Washtenaw and Packard). By August of 1943, over 12,000 workers had settled into new housing units.

Ford also eased their employment problem by hiring women. An ad placed in Somerset, Kentucky assured women they would receive “the same hourly rate as men.” Ford’s propaganda film “The Story of Willow Run” shows women working alongside men in several areas of the factory floor.

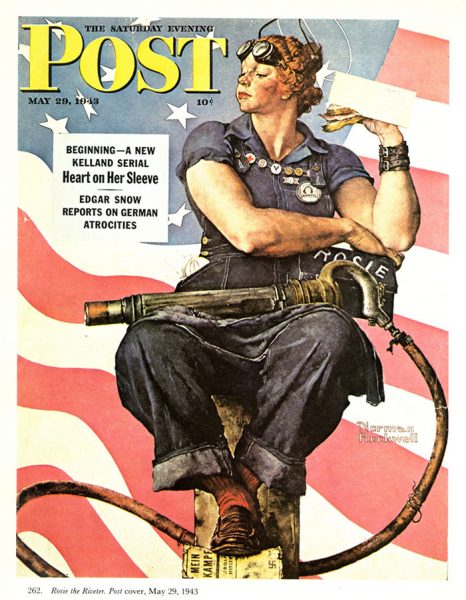

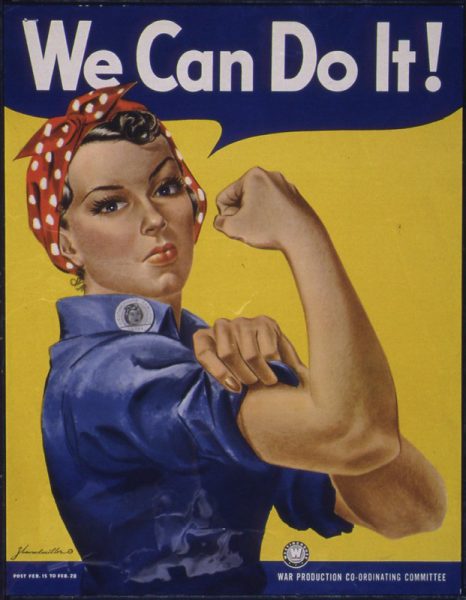

The most famous woman worker of the war, “Rosie the Riveter,” came from the Willow Run Bomber Plant. Rose Monroe, the widow from Kentucky, appeared in war bond promotional films after running into actor Walter Pidgeon while he was touring the plant. Riveters were responsible for installing over 300,000 rivets on each aircraft.

Women performed other tasks at the plant too, such as preparing tubing for the hydraulics, installing wiring, and shaping plexiglass. “Rosies” became the most well-known thanks to Pidgeon, the song “Rosie the Riveter” by Kay Kyser, and artists Norman Rockwell and J. Howard Miller.

Norman Rockwell’s Rosie (top) and J. Howard Miller’s Rosie (bottom). The women depicted in these pictures are not Rose Monroe but represent the same “Rosie the Riveter” character. Courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum and the National Archives.

With more housing and women workers came a more stable workforce, and the plant settled into a rhythm. Several of the plane’s 1 million parts were outsourced to other Ford plants in southeast Michigan. Even refrigerator manufacturers Gibson and Kelvinator contributed to the war effort by producing the center wing flaps and engine propellers on the B-24’s wings.

Willow Run was one of five plants building B-24s, with others in Oklahoma, Texas, and California. “Will It Run” became the most productive of all of them. By April 1944, three years after breaking ground, the plant was fueling up and testing a new B-24 every 63 minutes.

By the end of production in June 1945, Willow Run and Ford had built over 8,600 planes, almost half of the 18,000 B-24 Liberators ever built. Ford’s “The Story of Willow Run” bragged that the plant’s production was “relentless, unceasing, on time, as methodical as a great river fed by its tributaries.”

A worker inspects tubing at the Willow Run Bomber Plant in July 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

B-24s fulfilled a variety of uses for the Allies. They bombed Axis production targets such as the Ploiești oil fields in Romania. They transported fuel and soldiers to Europe. The Royal Air Force, which acquired several B-24’s through the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, attached lights to the underside of the B-24’s wings for night flying over the Atlantic. The B-24 was “instrumental” in defeating German U-boats, says Hotton.

It also became the “dominant plane” in the Pacific due to its flying range. The bomber could carry over 2,000 gallons of fuel, stretching its range to almost 3,000 miles. This proved to be a great advantage in a theater that stretched from the Bering Sea near Russia to the Solomon Islands near Australia.

The B-24’s improved range, speed, and carrying capacity brought more victories to the Allies, saving “hundreds of thousands of lives,” says Hotton.

“[The U.S.’s] efforts to have air domination so quickly” were pivotal in deciding the war.

B-24s built at Willow Run parked on the snowy tarmac, year unknown. Courtesy of the Ypsilanti Historical Society.

Ford produced its final B-24 on June 8, 1945, one month after the end of the war in Europe and three months before the close of the Pacific theater. Most B-24s were decommissioned and scrapped after WWII; the plane was quickly succeeded by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

Today, there are only 14 B-24s left in existence. Four of these planes were built at Willow Run; another two are airworthy. The Yankee Air Museum does not own any of these crafts, but it does boast a Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, a B-24 converted into a Navy patrol craft. This plane is currently undergoing restoration.

The only part of the bomber plant still standing is the finishing hanger, the 144,000 square foot section after the tax turn where planes were inspected, fueled up, and had their bomb sights installed. The hangar belongs to the Yankee Air Museum.

The museum recently returned to its regular visiting hours and encourages visitors to see their permanent exhibit about the B-24 and Willow Run, located in the main museum building. The exhibit includes the central fuselage and cockpit of a B-24, laid out to approximate the plane’s actual length.

These are the remnants are the manufacturing goliath that Ford built in record time. The rest of its legacy lives on in the local infrastructure built to accommodate it: roads that became I-94, housing that became beloved neighborhoods, a county health department. Eighty years after the plant rose out of soybean fields next to a small creek, Ypsilanti continues to benefit from the plant’s hard-earned success.