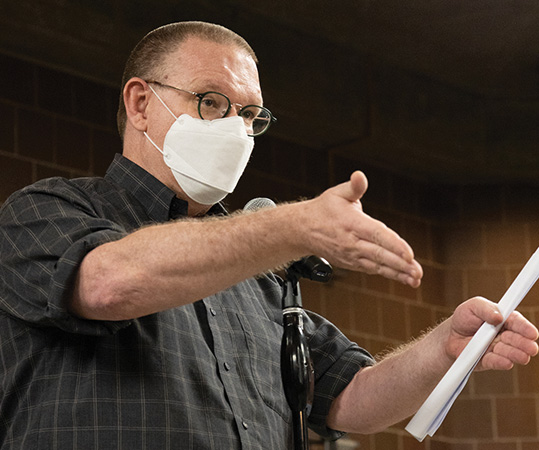

Ralph Johnson seizes the podium and addresses board members on oversight. Johnson wants to know who watches the watchers. Paula Farmer | Washtenaw Voice

By Jordan Scenna

Deputy Editor

Ralph Johnson waits in line for his turn to speak. He exudes patience, but behind the protective mask that shields his face, Ralph is flush with unease. His brewing anxiety is rooted in the Sheriff’s Department’s plan to ensnare Ypsilanti Township in a web of more than 60 cameras, aimed at every license plate that passes by.

The Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office has been embroiled in debate for the last five months with residents of Ypsilanti Township about installing license plate readers at every entrance and exit point around town. They plan to utilize LPRs to solve “serious” crimes and have said strict guidelines would be in place to prevent misuse.

Stationary license plate readers are fixed to traffic lights, telephone poles, or any high traffic area, and scan all cars that drive past, recording the plate, make, and model. Police can then cross-reference hits with a “hot list” of cars suspected of involvement in a crime.

The Sheriff’s Office has explicitly stated that LPRs would not be used to enforce civil infractions such as unpaid traffic tickets, which cities across the U.S. have done in the past to increase revenue with dramatic success.

The procedural guidelines, posted on the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s website, says LPRs are a “tool for the WCSO to capture evidence to assist with solving violent and non-violent crimes.”

The Voice was unable to speak with a WCSO rep to clarify whether civil infractions fall under the “non-violent” crime umbrella.

Citizens united

In an Aug. 24 report, Mlive reported that, “In community [neighborhood watch] meetings when proposed safeguards around the surveillance technology were explained and questions answered officials said they saw no ‘push back’.”

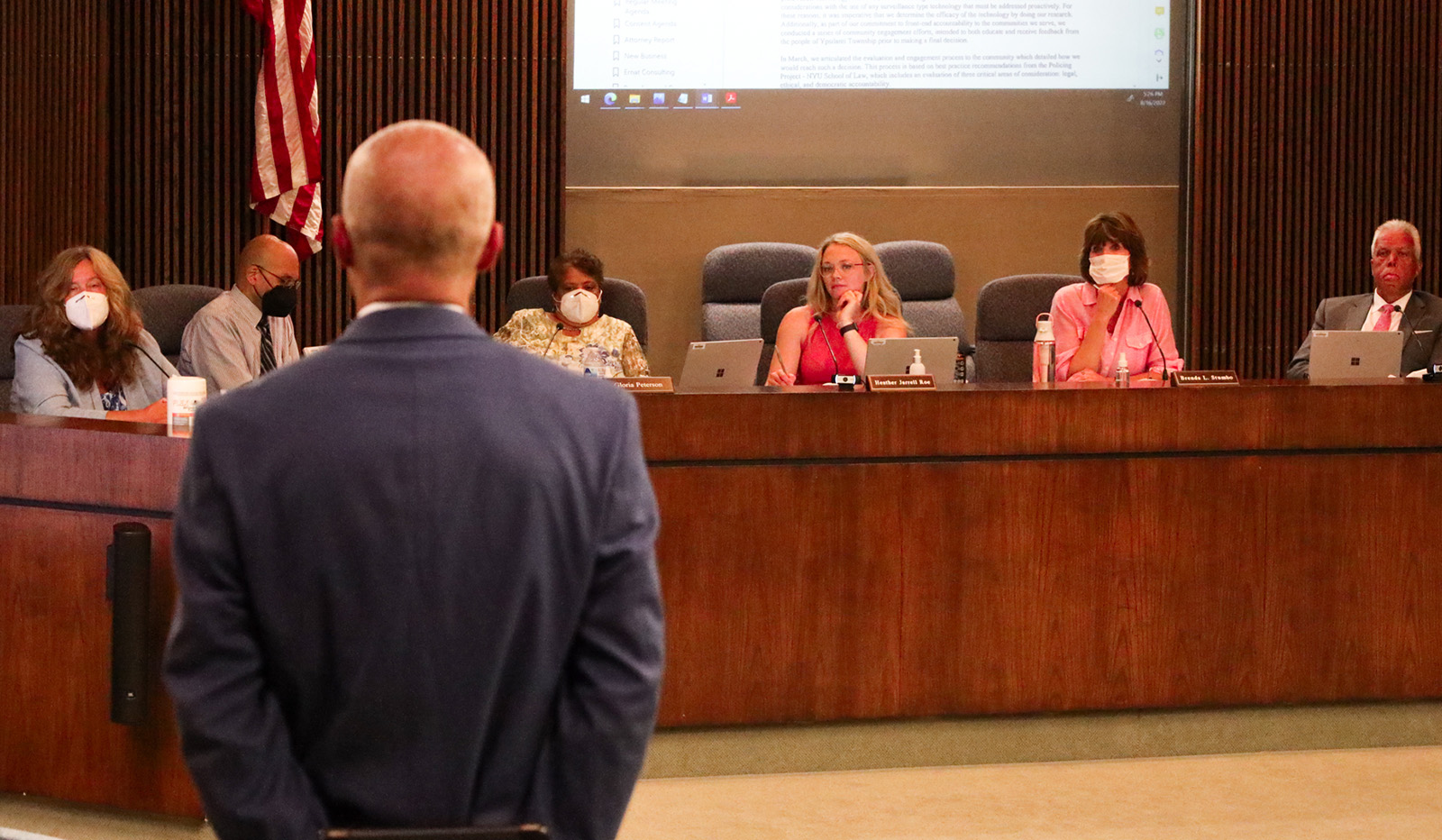

But on Aug. 16 the people of Ypsilanti leaned on Township board members with their collective weight.

Roughly 40 people attended the meeting, and of the 11 people that spoke, only one articulated the possible value of an LPR system. The majority voiced concerns of malfeasance or outright said they didn’t want the readers in their town.

An online survey conducted by the Sheriff’s Office revealed that 87% of the 1,148 respondents opposed the license plate readers, while only 10% were in favor. 3% were neutral.

Ralph Johnson, a Washtenaw County resident, had concerns over deputy misuse.

“There’s no question that this sort of thing happens all the time. What we need to know is exactly how someone will be held accountable [in case of abuse]. Will they no longer be able to use the system? Will they lose pay? Will they be fired?”

For Johnson, accountability was a major concern, and he expressed the need for community oversight, not just a check-and-balance system within the police department. Additionally, he thought the neighborhood watch meetings were given too much weight by the board and weren’t representative of the community.

Another Ypsilanti Township resident, Jonathan Hall, an assistant biology professor at Eastern Michigan University, demanded empirical evidence.

“The board should research whether this is needed, separate from the police and the vendors. Show us the data that proves this works.”

His skepticism was valid.

In a November 2021 study, the Independent Institute conducted an analysis of 16 years of data from Piedmont, Cali. about the effectiveness of LPRs and stolen vehicle recoveries. They found that less than 0.3% of “hits” translate to leads.

This means LPRs are gathering data on a lot of innocent people.

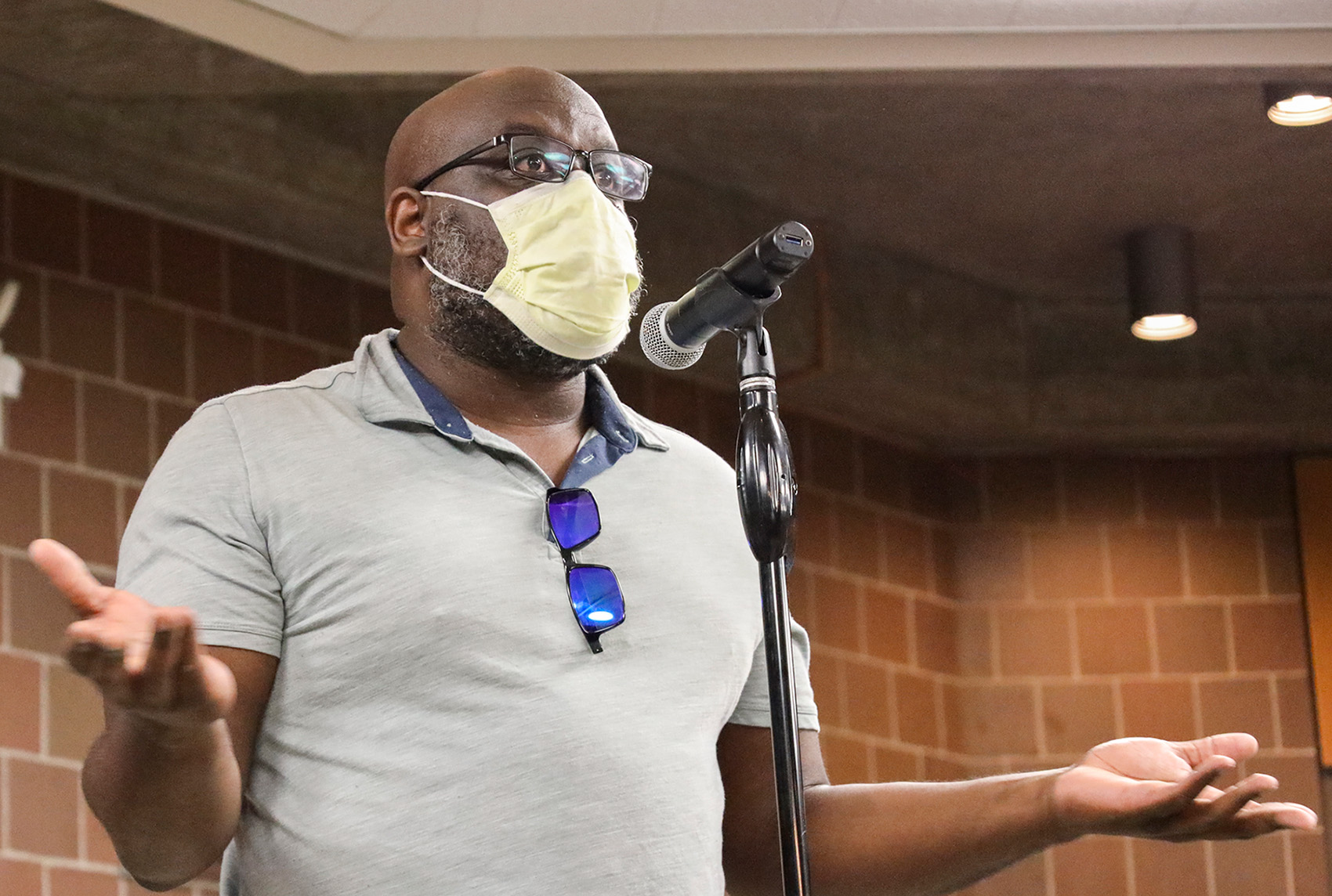

During the meeting, Derrick Jackson, director for community engagement for the Sherriff’s office, cited four local cases where the application of LPRs led to arrests of murder and car-jacking suspects.

In one instance a suspect was apprehended with the help of an LPR dragnet that Van Buren Township installed earlier this year.

The system holds data for 30 days, Jackson said, but it can be kept indefinitely for ongoing investigations.

Under the Uses and Accountability section of the guidelines, “All data captured by LPR technology will automatically be deleted after 30 days unless the data is pertinent to criminal or civil investigation.”

It is unclear why “pertinent” data would be kept to explore “civil investigations” if the LPRs are not going to be used for civil infractions.

A WCSO rep could not be reached for comment.

Sheriff’s Department official Derrick Jackson pleads his case to the township board. Jackson, director for community engagement, promised to only use LPRs for major crimes. Paula Farmer | Washtenaw Voice

Other concerns voiced to township board members ranged from intimate partner stalking within the police department, to the use of license plate readers to track women seeking abortions, either from out of state, or if Michigan law changes.

One woman said that the board didn’t do enough to promote awareness of the meeting and emphasized the lack of a Zoom option.

In response to the “strict guidelines” laid out to prevent exploitation, many residents wanted safeguards to combat eventual changes in department leadership; there was a visceral fear that the use of license plate readers would evolve from catching violent criminals, into a tool to recover unpaid court fees and traffic fines; or to target specific neighborhoods.

Last Thursday, an Ypsilanti Township official told the Voice the township is currently undecided on whether or not to move forward with the plan.

In a preemptive strike, Ypsilanti City leadership has signed an ordinance banning the installation or use of license plate scanning devices in city limits.